By Jackson B. Gingrich

EARLY AMERICAN INDIANS, as many prefer to be called, originated from northeast Asia. It is probable that a number of tribes, including the Lenape or their ancestors, crossed the Bering Strait from northern Asia during the warming period of the last Ice Age, which we estimate as ~12,000-15,000 before present (BP). Prior to that, the land bridge, though extensive and wide, was deeply frozen and provided only short shrubs and small mammals for sustenance, so crossing would have been nearly impossible. A broad swath of Algonquian-speaking tribes was conjoined in the northwest U.S. in what is today Washington, Oregon, and Canada about 10,000 years BP. Among this loose confederation were the Lenape-Nanticoke, Algonquin, Assateague, Wicomico, Accokeek, Iroquois, Piscataway, and others. These early Americans used oral recitals to convey tribal history to succeeding generations, so no precise dates of major events can be ascertained.

Some of the tribes spread to the mid- and lower Mississippi Valley by about 8,500 years BP.1 This area became Moundbuilders’ Indian territory, who were noted for building earthen and grassy mounds that are still visible today. After a relatively short stay there, perhaps several hundred years, some tribes, including the Lenape-Nanticoke and Iroquois, began searching for more fertile lands to the east.2 These ventures occurred during the Archaic Indian Period which extended from 8500 – 5000 years BP. The Lenape-Nanticoke and Iroquois teamed up for the journey east but went their separate ways in Ohio or Pennsylvania. But not before confronting and defeating the Allegheni Indians of Western Pennsylvania. After this, the two tribes split, with the Iroquois going north into upstate New York, while the Lenape-Nanticoke eventually settled around the whole Delaware Valley and into Delmarva. The Lenape have a tribal history in the Delaware Valley of at least ~8,000 years, and by the Woodland I Period (5,000 to 1,000 years BP) were the dominant tribe of Delaware. Later, it appears that the Nanticoke diverged and moved further southeast into Maryland and Virginia about 800 years BP (the Woodland II Period (1,000 – 400 years BP). However, the Lenape stayed north of the Indian River (DE), and along both sides of the Delaware River Valley as previously stated.

Their dialect was Algonquian, similarly to many other tribes in the East. The Lenape were closely related genealogically to other Delmarva tribes and occupied the whole Delaware Valley upriver from Cape Henlopen to northern Pennsylvania, then extending around the New Jersey side of the Delaware River to Cape May. There were also scattered communities in southeastern New York, including Long Island.

Wikipedia states that the Nanticoke were an offshoot of the original people (the Lenape) who in turn derived from the confederation of Algonquian-speaking tribes previously mentioned. However, this claim is rejected by the Nanticoke, who were also known as the people of the Tidewater. They were the first tribe to contact Captain John Smith in the Jamestown settlement of 1607-1608. It appears as rapid colonial immigration of Tidewater areas occurred in the 17th century, the Nanticoke were forced north and west into the Pocomoke and Nanticoke River drainage areas of Maryland and Delaware.

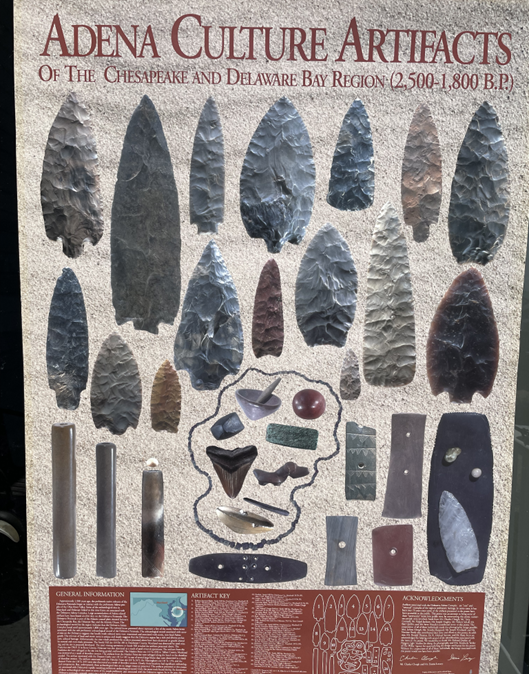

A third tribe, the Adena, existed as an entity in Delaware for a relatively short period from 2,500 to 1,800 years BP. They were a small tribe of a few hundred persons living mainly in Kent County north of the Mispillion River and west towards Frederica and Dover. They arrived in Delaware as an offshoot of the Moundbuilders of the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys. Despite their small numbers, they were considered more advanced than the Lenape in important ways, including toolmaking, pottery making, arrowhead and adze manufacture, and cultural sophistication. They brought soapstone (steatite) with them, which was prized by the Lenape for fashioning paintable pottery. The Lenape also admired Adena pottery because of its more exquisite designs. Going forward, the Lenape adopted Adena-style pottery into their own culture. The Adena also made unique short spears called atl-atl (Fig. 1) that were very useful in short range hunting of large animals. Moreover, they buried their dead in shell pits containing natural lime which deterred decomposition. Their dead were usually buried with ceremonial pipes, hunting points, and pottery. The 10,000 Graves site (also called Island Farm) at South Bowers Beach is thought to originally have been of Adena derivation, although it was claimed by both the Nanticokes and Lenape who protected it from vandalism in the 20th century. They lived a hunting, fishing, and agricultural lifestyle, and were believed to have shared their advances with the Lenape. Because they intermarried with the Lenape, they were eventually subsumed by the greater numbers of Lenape.

It seems likely that both Adena and Lenape tribes learned the art of oyster roasting, as numerous buried oyster pits were found in coastal areas inhabited by both tribes. A large pit would be dug in sand along the coast, lined with empty oyster shells and a commensurately sized wood fire would be built inside. After the pit was properly filled with very hot wood coals, rocks would be added and then superheated for hours. At that point, the rocks would be removed, replaced with live oysters, and once again covered with the hot rocks. The whole pit would then be covered with sand and

oysters would be cooked for hours beneath the hot rocks. The roasted oysters would by then have gray shells from the heat and be removed for a great feast.

Our local Lenape tribes were well settled in the east and already had an advanced culture by the Woodland I Period based on archeological findings from the excavations from many dig sites of Delaware. Among these sites was a proposed road cut for Highway SR1 to Rehoboth that bisected today’s Cedar Creek Rd. (DelDOT Reports, 1998, 2014).3,4 However, the Nanticoke also laid claim to this site. There was a legal battle over this historic Cedar Creek Rd. site, because two Indians had a rented homestead there from 1761-1814, who the Lenape claimed were from their tribe based on types of pottery artifacts present at the site and in deeper layers of excavations beneath the homestead. The Lenape therefore rejected the Nanticoke claim that was based on a report by Jay Custer,5 a DelDOT contractor and University of Delaware historian. The Lenape claimed that the type of prehistoric items unearthed at this Cedar Creek construction site, underneath many layers of earth, dated back at least to the Archaic Period (8500-5000 years BP), suggesting that they had inhabited the site for thousands of years prior to the arrival of the Nanticoke. Indeed, there were other tribes further south on the Delmarva Peninsula including the Wicomico, the Assateague, and the Chincoteague. However, we will focus on the Lenape and the Nanticoke, which the Europeans jointly (and incorrectly) referred to as “Delaware Indians.”5 As a result of the inter-tribal dispute, the original study was never published by DelDOT, and the information was not published until a second study concluded by Hunter Research, Inc. in 2014.3,4

The “Delaware Indian” designation was a colonialist name given to the Lenape and the Nanticoke by early white settlers. There were no obvious physical differences, but the Nanticoke Tribe considered themselves genealogically distinct and inhabited southwestern Delmarva starting about 800 years BP (during the Woodland II Period) along the Nanticoke and Pocomoke Rivers that drained into the Chesapeake Bay. As noted earlier, the Nanticoke were the Indians encountered by the settlers of Jamestown in 1608. As the whole tidewater area of southeastern Virginia and Maryland rapidly mushroomed with thousands of colonists over the next decades, the Nanticoke were forced further north into the Pocomoke and Nanticoke River basins in Maryland and Delaware during the 17th century.6

From the north in New York, the warlike Iroquois and Algonquins forayed south into northern areas inhabited by the Lenape, sometimes doing the colonists’ bidding in expunging the Mid-Atlantic colonies of the peace-loving Lenape tribes.

Chief Dennis Coker, the current chief of the Lenape, said a Lenape spear point dating to 23,000 years BP was found in a preserved mastodon 40 miles out from Ocean City, MD, where the continental shelf was exposed during the Ice Ages.7 The written documentation of this assertion is still under investigation. Chief Coker provided this information to support his idea that the Great Spirit “plunked his tribe straight into this area at least 23,000 years ago.” Of course, it is also possible that the artifact was transported there by natural forces and was not as old as supposed. It should be noted that mastodons were extinct by about 10,000 years BP.

The peace-loving Lenape (also called the “the ancient ones,” were thought to have spawned many other tribes among the Northeastern Indian Nations.

They themselves were divided into three geographic ranges – the Munsee People (“people of the stony country” – the area north and west of Philadelphia), the Unami (“people down river”) – the area in what became Philadelphia and suburbs. Moreover, there were two other minor Lenape tribes called the Big Siconese and Little Siconese, hailing from the Cape Henlopen and South Jersey areas (not discussed), respectively. Their dialects were all similar, but not identical (Figure 3). However, only a few tribal elders speak Unami (of Lenape origin), and there have been no known Nanticoke speakers for over 150 years.

The Lenape were noted for mediating differences among the various native tribes and were much admired by early European colonists for their skills in settling disputes.7 However, the Big Siconese, who lived in an area the Dutch called Horenkill (and later Zwaanendael).

These areas became known as the towns of Henlopen and/or Lewes. The first Dutch settlement was built as a whaling village by Capt. Peter DeVries, along with 28 of his shipmates in 1631. Capt. DeVries returned to England later in 1631 to gather more supplies, and when he returned in 1632 found the settlement had been destroyed by the Big Siconese. The story told was that a Dutch Coat of Arms, set as a metal marker, fascinated the Siconese Chief who carried it back to his village to fashion the metal into pipes, and in so doing, ruined it. The tribesmen, thinking they had greatly offended the Dutch, killed the chief in atonement. The Dutch settlers went to the tribe and told them they should have brought the chief to them for punishment. The Indians, feeling disrespected, returned to the settlement and killed all the settlers and destroyed all homes. However, the Big Siconese, seeing the much larger Dutch force, and fearing their powerful guns and cannons, began gradually vacating the area and establishing new villages further north.8

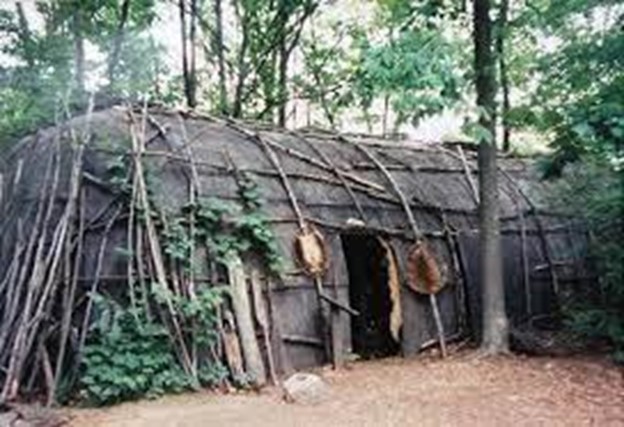

The Delaware Lenape inhabited numerous Delaware locations seasonally, inhabiting the inland forests during the winter, and coastal areas during the summer. Many had longhouses (Figure 4) that held 4-5 families or more for winter use. A village might consist of 10-12 of such houses (William Pike, personal communication).8

These villages were essentially within the inland areas of Kent and Sussex County.

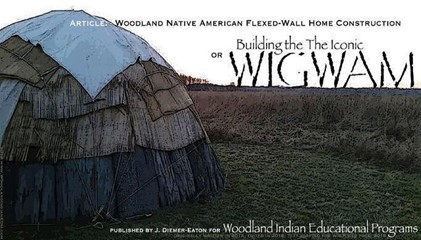

Wigwams made of wood were for single families and more for warm seasons along the coast (Figure 5).

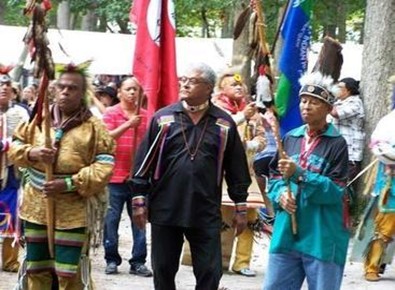

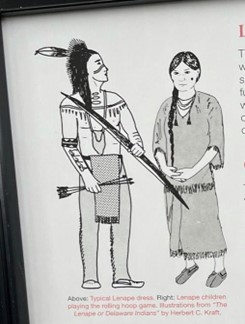

The Lenape displayed average heights of 5’1” to 5’7” among men, and 2-3” less for women.1 Both the Nanticoke and the Lenape had an oval facial structure with high cheekbones, tan skin, and broad shoulders.11 Clothing for men comprised breechcloths during the summer and fur robes during the winter. Women wore deer hide wrap-around skirts and shirts during the summer (Figure 6) and fur robes with leggings during the winter (personal communication by Mr. Sterling Street)9.Both men and women used bear grease as hair dressing and decorated their bodies with designs painted in various colors. Men, women, and girls adorned themselves with jewelry made of shells, stones, beads, as well as animal claws and teeth.6 During festivals, however, clothing was much fancier and ornate, as seen in the parade photo below (Figure 7).

Not only did both men and women of the Lenape and Nanticoke hunt and fish, but also women tilled the soil and planted agricultural crops during the summer11. Corn was the main crop, although squash, beans, pumpkins, tobacco and sunflowers were also cultivated. In fact, tillage was so intense that soil would be depleted after about two decades of farming, and clans would frequently relocate based on soil fertility.8 The Nanticoke often practiced crop alternation in their gardens, so that carrots and onions were planted in alternate rows in the garden (Figure 8). Therefore, pests of each row would be attacked by natural enemies in the alternate rows, an early method of pest management.8 The Lenape had a similar system called “the three sisters,” consisting of concentric rings of beans and squash surrounding a stalk of corn.9

Family lineages were traced maternally through the eldest woman, who also appointed and dismissed the sachems (chiefs), although former sachems were usually part of tribal councils which made the decisions. Because of short life expectancy, girls married at 13-14 years, while men married 3-4 years older. Not all marriages lasted a lifetime, and divorce was quite easily arranged. Women could simply place her husband’s belongings outside the family wigwam, or men could simply leave the home, and the divorce was settled. Men and women had traditionally different duties in keeping the home. Women trained their daughters, tended children, gardened, skinned/tanned hides, sewed clothes, cooked family meals, and collected fruits, berries and nuts. Men made tools and weapons, constructed wigwams or longhouses, built dugout boats, hunted game, netted and harpooned fish, and caught fish using dams.1 Fathers and older men would train their sons in hunting and fishing, as well as all the skills attendant to those activities. Women not only hunted and fished but were also the bearers of the travois that carried belongings for trips. However, men were considered the protectors of the tribe or clan.8

Spiritually, as with virtually all native Indian tribes, the Lenape and Nanticoke believed in the “Great Spirit”. They also believed that animals and plants had spirits that were to be respected. For that reason, many Lenape personal names referenced the names of their perceived animal spirits. Names were selected by each boy or girl as they reached puberty. They also believed that through their dreams they were enabled to see their ancestors, and peer into the past and future.3 The Lenape and Nanticoke believed it was their duty to husband their lands and resources and prepare for the lives of the next 7[2] generations, a long-lived view that spoke to the respect for life not only of themselves, but also their descendents.9

As the 17th century unfolded, the winds of change swept across all the areas inhabited by the Lenape and the Nanticoke tribes. The first real encounters were with Dutch and Swedish explorers and traders. As mentioned earlier, the Dutch had already settled in today’s Lewes area of Sussex County, which became the first town in the first state in 1631. The Swedes, under the leadership of Peter Minuit, the New South Company bought a tract of land near present-day Wilmington. The Company also established a settlement on Tinicum Island (very near to today’s Philadelphia International Airport). Swedish and Finnish fur traders (who traded with the tribes) followed and trading posts were established along the west bank of the Delaware River. In 1640, the Dutch sold their shares in the Company to Swedish investors. However, the Dutch still had ambitions in the area and established their own trading posts. Then, in 1655, Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch Governor of New York City led an invasion and captured all the Swedish settlements along the Delaware River.10

However, the Dutch soon lost their land claims to Great Britain10 because they provided no military support to protect their settlements. While the Dutch had fluctuating relations with the Lenape tribes, King Charles II in 1664 (Figure 9), had already given provenance of the territory to his son, the Duke of York. He in turn installed a local governor for the territory to manage the three lower counties (Delaware), in the person of Gov. Edmund Andros. Governor Andros resided in New Castle, the capitol of the three lower counties. However, in 1681, because of debts owed to Penn’s father, the King (stamp photo below) granted William Penn a charter to Pennsylvania and (officially, years later) the three lower counties (Delaware). However, this basically just recognized the de facto situation, because the lands were already occupied by British settlers. The grant was for land claims for Penn’s peaceful, and much persecuted, Quaker followers. However, the apparent dispute around ownership of Delaware’s Indian lands was dodged by William Penn, who did not want the responsibility of managing Delaware’s three lower counties, which Penn thought were too “unruly and diverse.”

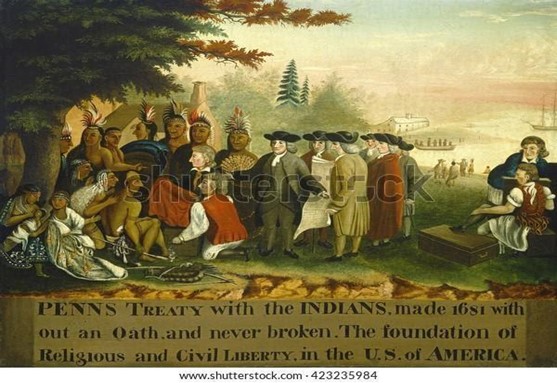

So, it transpired that Gov. Andros under the Duke of York continued his rule of the Delaware counties from New Castle, which remained the capitol in those times. The Treaty of Shackamaxon (in areas of Philadelphia (today known as Fishtown, Kensington and Port Richmond) was made under an ancient elm tree between William Penn and Lenape Chief Tamanend in 168211. This area was much favored by the Lenape because it was one of the tribes’ favorite meeting places and overwintering spots near the river. It is also a site of much legend and a famous painting by Benjamin West done ~90 years later (Figure 10).

Although the treaty explicitly stated only that the Penn colony and the Lenape would live together in perpetual peace, the Lenape soon learned that the Penn colony had essentially gotten title to their lands.

Penn’s treaty only granted the Lenape access, but not actual land ownership. Since the Penn claims were at first limited to southeastern PA, relations with the Lenape of that region remained good because Penn respected and practiced goodwill and friendship towards the tribes. He made purchase agreements with the Lenape that brought lands deeded to him under his absolute control, but he recognized Lenape lands and reserved tracts where they would be settled without ever having to be sold. Relations with European settlers remained good until Penn’s Death in 1718. Penn’s sons in 1737 reinterpreted an accord their father had reached in 1686 with the Lenape. The sons’ “interpretation” was that the original agreement extended to all lands to the north and west that could be walked in 1.5 days by “walkers” from Philadelphia. With trained and skilled walkers, this effectively added to the Penn family lands some 750,000 acres12.

The Lenape had already been retreating from Delaware and southeastern PA, but then the British made an alliance with the Iroquois Six Nations to drive all of the Lenape tribes to Ohio, Northwest Territory. The battle of Fallen Timbers, Ohio, in 1794, which the Lenape lost, effectively left them powerless, and they were sent to Indiana and beyond to resettle. However, some of the Lenape remained hidden in plain sight near small towns such as Cheswold (near Smyrna), joined Christian churches, and effectively went unnoticed until recent years, when they quietly reeemerged10. Besides losing their population to armed colonial forces, the Lenape were constantly fighting epidemics of smallpox, polio and other diseases of colonists, which virtually decimated (~90 % died of diseases) their resident population by 90 percent during the early 1700s.13

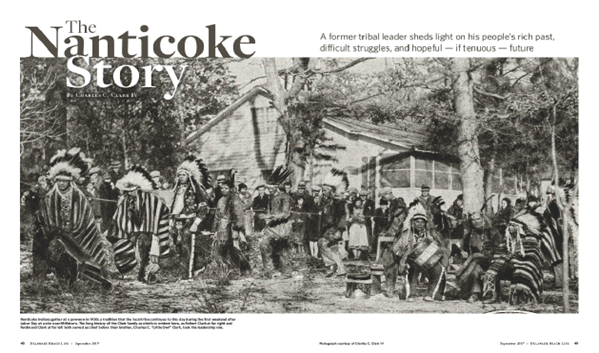

By the late 17th century, the Nanticoke Tribe was located primarily along the Nanticoke River and environs, and therefore the tribe became focused on living near the Chesapeake Bay, somewhat south and west of the Lenape Tribe. Much of the Nanticoke tribal history is accessible through the Nanticoke Indian Museum in Millsboro, DE (Figure 11). During a Zoom talk given by Bonnie Hall, an elder woman of the Tribe, on 25 March, 202114, we learn much about the early history of the Nanticoke. She spoke of the early history of the Mission and the first church congregation there in 1819 in St. George’s Chapel (but the Harmony United Methodist Church was not built there until 1891-2).

The Nanticoke joined the Christian Church, in part to blend in with the European settlers. The church in those days doubled as a schoolhouse for their children. Coexistence with the invading Europeans was breached frequently over land ownership. For many decades they watched as their lands became property in the European tradition, whereas the tribes believed it was common ground and that they were only giving license to use it to sustain life.15 Like other Indian tribes, Bonnie Hall told how the Nanticoke considered the Earth sacred, and how they communicated with the same “Great Spirit” of other tribes. As with the Lenape Tribe, they also firmly believed that their ancestors could speak to them through their dreams. However, after fighting against the invasive Europeans for many years, they ultimately decided that “going along and getting along” was the best policy for survival, even though they continued to hold onto many of their ancient tribal rituals, including the Annual Powwow Figure 12), which continues to this day. However, The Lenape decided to “hide in plain sight” in the farm community of Cheswold, east of Smyrna, as well as other towns such as Kenton. They also became Christians and intermarried, but still kept their tribal rituals, although only in private.9

The Nanticoke never celebrated Columbus Day, but rather started to celebrate Indigenous People’s Day on Oct. 14, 2019.8 They were recognized as a Tribe by the State of Delaware in 1881 (Wikipedia).

If you go to the Nanticoke Indian Museum, you will see their tribal history that goes back over 800 years, much of it predating their arrival in southern Delaware. The Museum has many artifacts, including ancient handmade tools, smoking pipes, arrowheads, and much more Figure 13). This evidence supports the conclusion that the Nanticoke were, like the Lenape, part of a strong and stable culture. Neither tribe were the savages that even prominent Americans, such as George Washington, portrayed them to be.1 The Island Field Site in south Bowers Beach, DE, was discovered in the 1920s during DelDOT road construction, but was only fully explored in the 1960s and beyond. It was considered to be a large and ancient cemetery of the Nanticoke Tribe that dated to ~800 years BP.15 In the 1970s the site was opened as a museum to the public, but had to be closed off because of vandalism. This cemetery held sacred value to the Tribe, and the Nanticoke persuaded the State to protect it from all but selected historical and archeological groups they approved. 1n 1986, therefore, the State covered the site within an oversize metallic pole building that has been closed to the public since 1987.15 In researching it further online, I found only one photo (Figure 14) of it being worked on by tribespeople and archaeologists in the 1960s and 1970s.

In a related presentation by Ms. Theo Braunskill during a Zoom presentation to the Lenape tribe1, it was learned that the average age of death of Native Americans in that era was 55, with the oldest remains belonging to a small number of people in their 70s. Surprisingly, the archeologists discovered that dental caries leading to heart disease was the leading cause of death. It was also learned that the site contained stones, copper, and arrowheads far from this local region, and it therefore concluded that there was a thriving continental trade network that went all the way to the west coast, north to Canada, and possibly even south into central America.1

The Lenape were not officially recognized as a Delaware “Sovereign Indigenous Nation” by the State until 2016. Even their religious ceremonies were not recognized by the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs until 1978. In fact, there have been a number of legal battles between the Nanticoke and Lenape since the discovery of a prehistoric site at the intersection of SR1 and Cedar Creek Rd while DelDOT was preparing for building the overpass there.5 This was discussed earlier, the ensuing legal battles have generally delayed the Lenape from getting official recognition by the federal and state governments, according to Chief Dennis Coker.7

In any case, what remains of both tribes today is a combined population of less than 700, although this officially counts only those who have at least 25 percent or more of Indian ancestry. There are also the Moors of the Kent and Sussex County, who are of mixed African-American and Native-American blood, but do not qualify as indigenous by the 25% standard of both Lenape and Nanticoke tribes.16 This subject is too complex to be fully explored herein. However, it should be noted that the Moors settled primarily near Cheswold (adjacent to the Lenapes) and in the Indian River Hundred, within close range of Millsboro. The Moors themselves were originally said to have mixed Spanish and African blood. However, distinctions from “true” Native Americans were often based on physical features or skin color, rather than on actual genetic lines. Needless to say, until after World War II, there were many disputing factions among these groups, all of whom sought State recognition, financial assistance, and power (Weslager, 1943).16

Despite the strife between white colonists and Indian tribes, in recent decades the tribes were recognized first by the U.S. Government, and then by the State of Delaware. This gave them the same status and rights of other tribes that had been given independent entity status within U.S. law. As a result, and after many years of legal battles, most recently in late 2021, the tribes were allowed to reacquire some of their own lands. The land costs were borne by a State Conservation Fund in conjunction with another private conservation group called the Mt. Cuba Center. The Mt. Cuba Center is a philanthropic conservation group that originated due to the efforts of the estate of Phillip DuPont Copeland and his wife, Pamela.17

The donated Nanticoke land is a 31-acre piece of mostly open land that abuts the area of the old Indian Mission School in Millsboro. The Lenape tribe received 11 acres of forest land near the Fork Branch Nature Preserve, not far from their current main settlement in Cheswold.117 Because these purchases were just announced on Nov. 28, 2021, plans for their use are still being considered, but lands will only be used to the benefit of nature and all tribespeople. Former Chief Natosha Carmine (Figure 15) of the Nanticoke and Chief Dennis Coker of the Lenape are both committed to not developing their areas for housing or profit.17 It is presumed that the new Nanticoke Chief Avery Johnson will similarly continue this policy. This welcome turn of events is a welcome advance to further the goals of both tribes, as well as healing some of the scars of the last 4 centuries.

References

1.Braunskill, Theo. 2021. Zoom Talk for National Women’s month by author, an elder of the Lenni Lenape Tribe March 20, 2021

2. Carter, Dick. 1976. The History of Sussex County, Part I, The Indians Take Control. Millsboro, DE.

3. Farmer’s Delight: an 18th century plantation in southern Delaware, Phase III Archeological Data Recovery, the Cedar Creek Road Site, Cedar Creek Hundred, Sussex County, Delaware, Chapter 7.

4.Hunter’s Research Inc. 2014.DelDOT Agreement 1535, Chapter 5.

5. Custer, Jay F. 1998. Uncited work at the Farmer’s Delight, an 18th century plantation in Southern Delaware, including archeological excavation data from the Cedar Creek Road site, Cedar Creek Hundred, Sussex County.

6. Kraft, Herbert C. 2005. The Lenape or Delaware Indians (New Jersey Lenape Lifeways, Inc. pp 29-35.

7. Personal communication. Jul 14, 2021. Interview with Lenape Chief Dennis Coker recorded via Zoom at Slaughter Beach, DE, fire hall.

8. Weslager, C. A. 1972. The Delaware Indians: a History. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ. 59pp.

9.Personal communication. May 25, 2021 with Mr. Sterling Street, Nanticoke Indian Museum Coordinator. Millsboro, DE.

10. https://nanticoke-lenape.info/history.html:~text=The peace-loving Lenni-Lenape, tribes, accessed May 1, 2021.

11. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/treaty-of shackamaxon-2/accessed May 18, 2021.

12. Fisher, George. W. The Walking Purchase. Philadelphia Reflections, accessed May 11, 2021.

13. Licht, Walter, Mark F. Lloyd, J.M. Duffin, & Mary McConaghy. 2020. The original people and their land: the Lenape, pre-history to the 18th century.

14. Hall, Bonnie. 2021. Zoom Talk for National Women’s Month by the author, elder of the Nanticoke Tribe, March 25, 2021, Dover, DE.

15. Custer, Jay. Fall, 1990. A Re-examination of the Island Field Site (7K-F-17), Kent County, Delaware. Archaeology of Eastern North America. (Vol 18) JSTOR 40914323.

16. Weslager, C.A. 1943. Delaware’s forgotten folk: The story of the Moors and the Nanticokes. University of Pennsylvania Press. Philadelphia, PA. 215pp.

17. The Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2021. Washington, DC.